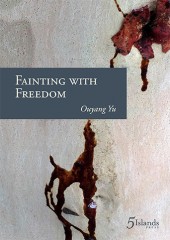

Fainting with Freedom

by Ouyang Yu

Five Islands Press, 2015

Ouyang Yu is a prolific writer whose combination of occupations – poet, novelist, translator, academic – gives some context to this book’s obsessive engagement with word, language and meaning. His biographical note mentions that he came to Australia at the age of 35, and there’s a pervasive trope in Fainting with Freedom of a stranger-in-a-strange-land’s curiosity for the materiality of language and its malleability: something akin to what Kerouac once alluded to when he described his relationship to English – a language he didn’t learn until he was eight – as a tool he could very consciously manipulate as necessary for effect and meaning. For Yu, this fascination is not limited to the experiences of a foreigner acculturating to a new socio-linguistic circumstance, but goes much further and deeper (presumably due in part to or concomitant with his work as a translator and teacher), investigating and playing with the complexes that emerge from the interaction back and forth between languages and his own movements across them. What emerges is a burgeoning sense of a meta-culture, not merely a bigger, hybrid, Chinese-Australian context, but a richer, more meaningful bilingual world available to those with the knowledge and awareness to perceive it.

For the rest of us, the contents of Yu’s poems offer tantalising windows into that world, especially in combination with his formal versatility. In form and style his poems are typically full of disruptive, unexpected lines, deploying enjambment, malapropism, skilful grammar (as well as wilful disregard for grammar) in service of profundity, humour, and intellectual interrogation. Moments emerge from Yu’s work as a translator and as a language teacher, and his fascinations capture not only an other’s perception of his second language and culture, but also a revision of his first language, and glimpses into parallels (as well as enormous divergences) between the two. There’s something enormously heartening about reading such a living, adventurous book published in English in Australia that can nonchalantly presume the relevance of a treatise on individual Chinese words or characters, or their relationship with English. Poems like ‘Talking about ’ and ‘Round’, with their matter of fact use and discussion of non-Latin characters, as well as non-European cultural referents, expand the palette of the possible for contemporary Australian poetry.

Perhaps the poem most emblematic of the book as a whole, ‘Round’ in particular wrestles with the inexactitude of translation, the ‘primitiveness’ of English and its inability to capture the nuance of a two-character Chinese word. The opening and closing stanzas summarise much of the story:

One student stood up and said,

“the subtle factor that makes live endurable” is not right

as the word “endurable” is not a correct

translation of the Chinese characters yuanhua

(…)

on his way home, the teacher was defeated again

when he thought of the impossibility of match

making the two languages in this single expression

that describes a person’s unctuousness, like oil or an eel

or that denotes life’s smoothness

in a round manner

as round

as a ball

Ostensibly about translation but produced for an English (only) speaking audience, this poem is as much about the futility of trying to express anything in any language, the flawed nature of language as a system, the unbridgeable difference between the uniqueness of individual aesthetic perception and the conventionality of language.

Elsewhere, at first encounter ‘Serendipity’ (particularly located as it is in a section called ‘Mathematics and Fog’) looks wilfully difficult, like a puzzle of typography as much as one of language:

it’s not that i don’t like it i actually do i mean the film that i saw tonight

it was actually a quite funny word when i first heard it

i thought it had something to do with being senile like senile dementia

It proves, however, to be quite a straight narrative about a night out at the cinema, a condensed memoir, meditating on this one word (and film of the same name) to explore the speaker’s relationship with life, work, marriage, friendship, and transnationalism. At its heart is the single brief line, ‘did you see it just for her?’, a question posed by the speaker’s wife that betrays a glimmer of tension in their marriage, a conceit that alters the light cast on every other part of the poem, demonstrating a deftness with narrative detail, just the right amount, that belies a novelist’s feel for drama. Such careful and attentive use of story, particularly in those poems in the book that are so strongly located in modern urban settings, combines with the linguistic play evident throughout the book, to offer a tangible sense of the here and now in which these works were created and exist.

Opening with ‘Manufactured by no one but this/Is a morning that harks back to 1787’, the poem ‘A cloud’ similarly manages to invoke multitudes from small, precise detail (in this case, mention of the year prior to British invasion invokes the Australia of pre-European colonisation and pre-industrialisation, in part as a proxy for pre-pollution). This starts a riff that culminates half way through the poem with: ‘The city that is changing rolling into/a nation that soon disintegrates and fragments/in multiple communities of digital photographs.’ Such striking power to sketch an entire national history from colonial pre-nationhood, through to the contemporary era of multiculturalism and social media, and tell it without dull prosaics, is one of the key powers of this book. Moments like these emerge continuously, seemingly effortlessly. Later in this same poem Yu flexes his talent for Steinian word play and linguistic interrogation, an awareness of the language as a toolbox or machine that can be repurposed through close and careful modification: ‘cloud and rain, cloud into rain/clout encapsulated in the rain’.

At times Yu’s urban lyric pieces recall Lorca with the quiet intensity of their observation, and the modest yet clever use of metaphor and simile. Such pieces also demonstrate an appreciation for one of the fundamental purposes of artistic experimentation: application. Where elsewhere in the book sentiment and content are overtaken by grammatical and linguistic play, in a poem like ‘The evening walk’, Yu’s awareness of the power to disrupt or extenuate meaning by manipulating word order, line breaks and voice, enables the poem to more deeply evoke experience in the reader. Line combinations like ‘the air is strong with horse/shit’ capture brilliantly the slow-seeping disruption of an idyllic rural moment by the dawning awareness at first of something bestial, and then more precisely of just which aspect of the beast is present. The delicate play and balance between humour and earnest quietude in this poem suggests the author is closely familiar with needing time for reflection in order to make art, while still living in the contemporary world. Similarly, ‘I’m feeling sad tonight’ manages to create a simultaneously earnest, deeply felt confessional moment, and a parodic critique of the same:

“I’m feeling sad tonight”

I turn around but see no-one saying that

“I must admit I have not felt this way for quite some time

As night is gathering its dark colours

The earth is taut and loud

With crickets like someone has switched a symphony on

Two died in the same year

Closest to my skin

I’m going somewhere else alone

To celebrate my 50th

Birth day

As he said he would do his 21st

A family of loners

In a rootless

Country

Loud again

Before death”

My heart lowers its head to listen.

It’s a quite extraordinary poem. The apparently arbitrary form – a blank line after every couplet – seems to contribute little until the final couplet, where two lines separated grammatically by the end of the quotation are brought together. That pairing drives home an intense profundity, the sort of brief, dashed-off moment of deep clarity characteristic of a lone poet like James Wright: “Before death’/My heart lowers its head to listen.” In turn, the use of the long-running quotation as a framing device emphasises the self-mockery of the opening lines, but particularly through that final coupling – half within the quote, half without – the same device also serves to intricately explicate the dichotomy a fearless experimentalist must feel when confronted with a desire to express earnest confession in verse. Yu’s slightly odd word manipulation – the synaesthetic ‘see no-one saying that’, or ‘Birth day’ as two words – recall once more his obsession with language play, but also evoke that ‘family of loners/In a rootless//Country’ and the cross-cultural uprooting (and perhaps attendant isolation) this poet has gone through. The use of ‘rootless’ in particular is strikingly clever, at once a near-cliché in keeping with the running parody of the confessional, but also so evocative of Australia and the strangeness of its vernacular – what does it mean in this particular culture to be alone and ‘rootless’ on a night of celebration? Indeed, to follow that word with the single-word line ‘Country’ approaches the Shakespearian in both bawdiness and skilful wordplay.

This book contains microcosms of alertness to the oddity of language as language, the arbitrary way meaning is distorted or inflected by unfamiliar acts of repetition, the use of phrases grammatically correct but somehow socially bizarre/inept, or the inappropriate use of passive or active voice. The actual subject of many of the poems is books and writing, literature or art as convention, with a particular concern for the non-creative aspects of the creative arts as an industry. In ‘Paintings’ for example, Yu calls out the exclusionary nature of acquired taste in a single line: ‘the eyes have to be trained but the names are more important’.

The second section of the book, titled ‘Leaf or fallen bank’, is preoccupied with questions of authorship and authenticity, while also making fun of arguing for a final position on these:

books, according to him, are not worth writing, having written one book that went back many centuries examining a time similar to ours in every aspect of time except the sound of their voices, which, unfortunately, have not been recorded, and the details that could not have been noticed by themselves or filed away (‘Books’)

As is so often the case in this book, here Yu seems to be revealing an endless fixation with investigating the absolute truth of things that are fascinating because they have no absolute truth.

The playful self-deprecation in this book feels honest without being earnest, self-critical without being self-effacing; subtle but showy. ‘Banality’ for example, makes art of email spam with a flight of fancy into the repercussions of seriously considering an unsolicited offer of marriage: ‘If I were to marry you I would have had to divorce (…) if I were to re-marry I’d have to bear/with all this day after day after night after night’, and ‘what is this based on except I stayed up late or went to the (online) market’, end the prevarications through banal email interactions with the closer, ‘I want to disappear into creative/banality just gauge how close the bin is to my brain’. Yu’s is an honesty that couldn’t be otherwise; the whole value of his investigations seems to be in getting to the truth, not of objective ‘fact’, but of subjective perception and reception. The minutiae of the everyday (and the timeless) are fair game in this endless, unending quest to expose the fact that the referent is always ultimately deferred. Life is in the living – or in the becoming, might be another way to put it.

The subjects in this book are unrepentantly contemporary, with references (and hyperlinks) to Wikipedia, current politics, and matters of popular culture like the SBS-syndicated Chinese dating show Feicheng Wurao. Amongst such material, the natural world also makes appearances, yet in characteristically unique ways. Yu’s ecopoetics is one of problematics, and both the inevitable collisions between human culture and nature, as well as the timeless disregard the former has for the latter, inform his investigations of each domain. In ‘Self publishing’, for example, he critiques our arbitrarily gate-keeping literary culture by noting that, ‘birds never remain quiet because they don’t get paid for calling’. After admonishing at length the ridiculousness of worrying about the legitimacy of self-publishing, and citing numerous canonical authors who are guilty of that very crime, he closes summarily with, ‘Now listen, to the rain self publishing again as it did 3000 million years ago,/on the page that is my roof’. Meanwhile in ‘Installation 001’ he indicts both our artificial sanctions on what is aesthetically valuable as well as our concomitant ignorant misuse of the natural world:

you want to cut this roadside slope with wild grass and a few trees and relocate

them into the national gallery

you want to cut that sky where a cloud is so big it bursts the car window and

install it inside the brain of the country

you want to pull the lone tree by the root and stand it in the middle of all galleries,

blocking the view

At once wholly contemporary and somehow timeless, Yu’s approach doesn’t interrogate the interactions between the human and ‘natural’ so much as expose the hierarchy: that is, the artificial and therefore apparently subordinate human world, subordinate to (or just a pale shadow of) the totalising essentialness of all-that-is-not-human. We might debate amongst ourselves whether self-publishing our art removes its value, but in the meantime the fundamental beauties of reality – rain, birdsong – don’t have time (or need) for such crises of worth; they simply are, they exist and they act because they must. Yu seems to be telling us: if your art is not a function of your essential self, if you need ponder whether you should be doing it, you probably shouldn’t.

This book as a whole zooms from the macro to the micro, the personal to the national, in a way that feels frantic, encyclopaedic, and entirely subjective. Reasserting the value of the subject in the living world seems to be a driving mission of the verse. Whether or not we can describe the ineffable, or comprehend it, to exist is to know the ineffable exists. This book is a celebration, a condemnation, and a defiant incitement to go with boldness, to be amongst it.

*Michael Aiken is a writer living and working in Sydney. His first book, A Vicious Example: Sydney 1934 1392k1-1811 1682k2 and other poems, was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Kenneth Slessor Prize for poetry.

**From Cordite Poetry Review at http://www.cordite.org.au

Reblogged this on Manolis.