O Sonata: Rilke Renditions

by Chris Edwards

Vagabond Press, 2016

The Bloomin’ Notions of Other & Beau

by Toby Fitch

Vagabond Press, 2016

Chris Edwards’s O Sonata dwells in the vortex of the underworld, plumbing the depths of the Orpheus and Eurydice myth and resetting the entrails of Rilke’s Sonnette an Orpheus into a crossword puzzle ready for consumption. In the eponymous sequence, Edwards offers up a renewal of the Orpheus (also known as ‘the futile male’) myth to signal his reconsideration of repetition and originality as the basis of a literary revision – releasing a suite of renditions that purposely misinterpret, transliterate and obscure. Set up as an intertext to Rilke’s original sequence, Edwards’ rendition is animated by forces that teeter precariously on the edge of construction and destruction, or as he makes explicit in his opening poem:

a vortex

Turning on the same old Still point – we really tore up

That dungeon.

However, well before his ‘long climb from Hades,’ Edwards provides the context from which his poetic revision takes leave:

rendition | rɛnˈdɪʃ(ə)n |

noun

1. a performance or interpretation, especially of a dramatic role or piece

piece of music: a wonderful rendition of ‘Nessun Dorma’.

• a visual representation or production: a pen-and-ink rendition

• of Mars with his sword drawn.

• a translation or transliteration.

2. (also extraordinary rendition) [mass noun] (especially in the US)

the practice of sending a foreign criminal or terror suspect covertly to be

interrogated in a country with less rigorous regulations for the human

treatment of prisoners.

ORIGIN early 17th cent.: from obsolete French, from render ‘give back, render’.

The combination of this definition with Rilke’s original poetics creates an immersive reading of the fluid relationship between repetition and originality. As Julia Kristeva elucidates, ‘each word is an intersection of other words where at least one word can be read’, and in poem 7, Edwards readily deploys this idea:

Bid[s] verboten and adieu. Your best alternative lingers in this here

remedy for Turning: Do not default. The remainder’s a black

Hole hollering Hey, Frankenstein, halt!

The amalgamatic nature of verboten and adieu are key here. Rather than simply translating the poems – which Edwards, in a podcast for The Red Room Company, argues is ‘not possible’ – he ventriloquises the language of Rilke to the purpose of repetition and ‘malaprop[ism]’; but more on this later. At the same time, the blending of Germanic and French diction does as the antecedent example implores: it does ‘not default’, in fact, the suite of renditions resists traditional translation and semantic form. Throughout these inversions, Edwards has experimented with these terms to the purpose of linguistic innovation and textual challenge. What I mean is, the basis of Edwards’ collection is betwixt and between the impulses that are inherent in Rilke’s myth: a parable not to look back; that which is verboten [forbidden]; and the fragility of mortality which we must remember and to which we must bid adieu [farewell]. Further, Edwards makes it apparent that these terms are rendered meaningless through the implementation of ‘and’, the subject acknowledged fleetingly in verboten before being dismissed in adieu. Such conditions establish Edwards’ consistently disjointed voice within the ‘vortex’ that is O Sonata, rumbling and tearing up expectation, unburdened by narrative curtails and ‘turning on the same old Still point’. In this sense, Edwards’ rendition is a feat of originality, no less original than Rilke’s; the only difference between O Sonata and other texts is that Edwards is acutely aware of his source material, and makes the reader implicitly aware of this.

In poem 2 Edwards acknowledges the futility of translation:

As for that Big Stink we approach – again? – it’s Lies they tell me

to fix myself fast to …We’re here, Madam. My chain …

When compared to the corresponding passage in Rilke (1.2):

enfinden noch, eh sich dein Lied verzehrte? –

Wo sinkt sie hin aus mir? … Ein Mädchen fast …

It becomes increasingly clear how Edwards’s revision is not based in linguistic meaning; rather, his poetry weighs the silhouette and homophonic possibilities of the word, to weave a mistranslation that systematically disrupts consistent meaning and interpretation. In this way, Edwards oscillates between the construction / destruction imperative I outlined earlier, utilising Rilke’s poems only as a measure for himself and as a springboard for his own journey into language.

I find myself lost in the systematically obscure and inconsistent impulses with which Edwards climbs from Hades. The meaning of his text is veiled through intricate language barriers, and like Eurydice, true understanding is always just out of sight. Perhaps this is because, as Kristeva suggests, the literary word ‘is an intersection of textual surfaces rather than a fixed point’ – Eurydice perpetually vague and indistinct because the path to Hades is set on dual plains of ‘what Will be’ and ‘it has-been’. It speaks something of the significance of the fragment – the power to absorb and transform, distinct from context, outside of time and the necessity to respect the autonomy of these threads. Edwards’ quatrain at the beginning of poem 16 seems to be a tribute to this:

Dumb, mean and Fiendish, I bite into my sandwich. Wait …

I could have made the Words and Fingersign gesture one

always makes outflanking the opposition. Instead, I go

Swiss Cheese and veal, gristle and frog’s Tail.

In this way, Edwards translates his way into the language to make the words do something other, something more than representation. He calculatedly matches syntax and meticulous sentence detail, to return to the source text – only to augment and extrapolate the well-revised, futile-male myth and make it ridiculous. As he writes, ‘much is to be said here […] of the role of Malaprop[ism]’, demonstrated in the parallel excerpt:

Du, mein Freund, bist einsam, well …

Wir machen mit Worten and Fingerzeigen

uns allmählich die Welt zu eigen,

vielleicht ihren schwächsten, gefährlichensten Teil.

Throughout O Sonata, Edwards has created a vision in which the duality of the original and its revision are reciprocal, as he compounds in poem 31: ‘With someone one Goes waltzing, with oneself one wanders.’ Accordingly, Edwards appears to be commenting on Rilke’s rendition – and likewise, as improbable as that is. Take the first tercet and part of the second from Rilke’s poem 1.16. He states:

Sich, nun heißt es zusammen ertragen

Stückwekr und Teile, als sei es das Ganze.

Dir helfen, wird schwer sein. Vor allem: pflanze.

mich nicht in dein Herz.

In my rough translation, this amounts to (retaining the original punctuation and line length):

See, together we must endure it

These fragments and parts, as if a whole.

Helping you, will be hard. In particular, plant

Me not in the heart.

This translation hints at the essence of Edwards’s O Sonata and serves as a metaphor for writing a rendition. Being made of language, O Sonata is embroiled in the particularity of fragments, their subtle nuances and connotations, and to the furthest point of ingenuity it bleeds the idea that words have the power to dictate their own meaning. As single entities unto themselves, the poems’ internal logic is destructive and constructive; it considers the original and rendition together, but ultimately as separate. Edwards invites us to see how syntax has the power to unhinge and re-charge, the liberal capitalisation of words injecting the unexpected and signalling pause. So much of these poems must be weighed up in individual words, the single thread which has the power to bind and destroy the ‘whole’ that is at the heart of Rilke and is avoided in O Sonata. Edwards’s echoes back through the vortex, or more so across the page, ‘Very well: please / meet me at the Help desk.’

Edwards plays with the interpretative qualities of rendition, the sonnet form and O Sonata, pun to boot. The sonnet, traditionally divided into two; an octet followed by a sextet, is carefully sliced into four sections, resolving to quatrain, quatrain, tercet, tercet. This unfamiliar formation is taken directly from the musical sonata form. Translation has purposely been transmogrified to resist the necessary rhyme scheme of the sonnet, and replaced with a rhythm that ‘wheezes no it waltzes through the rattled / interstitial dark’ and behind the poem. The idea of resonance is fundamental to Edwards’ mistranslation, as in the collection he considers Rilke’s lyrical impulse, and turns it on its head, imbuing the sonnet with sonata constructs, and illuminating an ABBA rhythm enmeshed in four divisions of the poem. This clever and attentive conveyance of the performative functions of rendition is especially interesting when Edwards’ sonata is set against its cantare [to sing] counterpart, as the thematic drive of Rilke’s sonnet is embedded in lyrical impulse: ‘O Orpheus singt!’

Time and again through O Sonata, Edwards’ fidelity to roots and singular attention to detail demonstrate his exquisite grasp of language and sound. His augmentation, in accordance with Rilke, speaks on polyphonic levels; compare the opening line of Rilke’s poem II.5, ‘Blumenmusk, der der Anemone’, and Edwards’ response, ‘Bloomin’ muscles, they’re their own worst Enemy’. This comparison makes it clear that Edwards has the animating power to sustain connection through the purity of sound and shape; employing the phonemic qualities of the morpheme, ‘Blumen’, to create ‘Bloomin’, and still remain separate enough to create a secondary Hades from which to offer up to a ‘zooidal’ unification of the futile male and traditional myth.

Ultimately, I interpret O Sonata as an impulse in of itself, a re-presentation of the perilous path to the underworld that is now well trodden and ‘working at a wonky angle to the Zebra Crossing’. This image suggests that the Orpheus and Eurydice myth is nebulous, but also precariously stuck between crossroads, a scene juxtaposed by leaving and going. In this way, the necessity of rendition lies not in semantic meaning, but the possibilities that are just beneath the surface of a sound, a word, syntax or just on the other side of the Zebra Crossing. The combination of Sonnette an Oprheus and O Sonata signals that revision is an endless repetition onto itself, the source text and translation reliant and dismissive of the other, as in the final tercet of poem 54:

Should dickhead want to dance and Iridesce and get verbal, you can

always call on the Zoo to call on Erda to sing sadly: Ay Caramba.

Alternatively, you can spruik what Was as what Will be: it has-been

From one side of the road to another: Toby Fitch’s The Bloomin’ Notions of Other & Beau. In this rendition of John Ashbery’s translation of Illuminations by Arthur Rimbaud, Fitch has created a multiversal pathway into another inversion of the Underworld, or maybe a ‘nether nether’ world as it pertains to Australia. Fitch ploughs Illuminations as ‘fertile ground in which to grow Bloomin Notions’, and presents the land Down Under in a chaotic and continually metamorphosing shroud of visual and sensory aesthetics, to make a sequence taut between social disruption and transcendence.

In the final stanza of Fitch’s opening poem, ‘After the Orgy’, we get a sense of some of the key themes encountered in Edwards’ collection:

Voodoo & u who peer at my cash my

precious poor lark’ll hit the ceiling we’ll traverse

toilets dissing the clock

wise anti-delirium & go back

Down Under where the rest sank Freud

après the ludic deluge

ici aussi

totes

From the word, ‘Voodoo’, we are embroiled in the intrinsic and ritualistic modes of the book. Fitch’s Bloomin’ Notions is connotative of an effigy with which he invokes Rimbaud’s rebellious spirit and language, only to turn it upside down, hijack and re-verse. The movement of the above poem is vital to this effect: the vivid images (toilets dissing clocks), abruptness (‘where the rest sank Freud’) and construction on the page (oscillating back and forth in time with the ‘ludic deluge’) speak to the nature of Fitch’s Bloomin’ Notions; a real hybrid of ever-shifting parameters, implicated in free verse because this is the site of exchange and intersection. But this stanza does not pretend to be or do anything else; rather, Fitch spirals inwards, to the language of Rimbaud (go back), and resurfaces, ‘après the ludic deluge’, in circadian convulsions that mark the uncanny disposition of these poems as simultaneously old and new.

Take, for instance:

I is an / ugh it’s an ignoramus

jamais jamais u say / or maybe nether nether

Its inland sequel is counting on this Eur

optic allusion to echo it &/ or braise it w/

outsourcery in terror pots of ennui & rain

flowers overtly peer out

no less ensorcelled than stoner food

So naturally some cat

In this excerpt from ‘After the Orgy’, Fitch recognises his source material, abstracting Rimbaud’s ‘je est un autre [I is an other]’, only for the reference to be rapidly halted by a forward-slash. In this, Fitch perceives correspondence, preserving Rimbaud’s words, more or less, only to splay them out on the page, offering up the viscera of the original, before systematically dismembering and converting. In their place, Fitch creates a series of poems that suggest that the clean slate afforded in Rimbaud’s narrative, ‘After the Flood’, is no longer available. Rather, Bloomin’ Notions’ starting point is not the biblical flood, but the rapturous moments after climax. The seeds sewn in fertile ground are ejaculate, and what peers out is stagnant, circling around the loanword, ‘jamais’.

The French term oscillates between definitions of always and never, bound up in the referential past and subjective present of Fitch’s pastiche proclivity. Of course, in this paradox of the ‘mercurially deja’, one feels like Rimbaud’s mother after reading A Season of Hell: ‘What does it mean?’ The answer is varied, and fits succinctly into Rimbaud’s response: ‘It means what it says, literally and in every sense.’ In any event, Fitch expounds the imagined destruction of ‘After the Flood’ as necessary to create his ‘optic allusion [and illusion]’, and also as superfluous because the flood was mixed with sin and discharge.

Still wet from the ludic deluge, we encounter Fitch’s ‘In Fancy’. In this poem, Fitch augments the homophonic qualities of Rimbaud’s ‘Enfance’ to ‘blow open the safe of childhood’, and drag us back to the past, before we drone forward into ‘car / nations either plastic or dead’. It is set out on the page like a child’s shape-sorting toy:

Fitch counterbalances the waves of metonymy and form equally, filtering down the shape-cum-stanzas to a fanciful discourse bent on creation, reflection, repetition and ambiguous destruction, in this order. As we move through the poem we encounter the construction of ‘red & / black monstro-cities’. Here Fitch leaves a breath that serves as a comma, his use of punctuation minimal and frugal, ‘clogging the way back’ (but to what exactly?), before reflecting on ‘a sea a terror a prayer’, timelessly attentive to ‘sonar clock bells’ that ‘has no ring to it’ and the ‘anvil of / a shadow colony w/ sluice gates’. I want to stress the ‘sluice gates’ in the concluding hexagonal stanza. That Fitch’s final shape should contain a conduit with which to hold back a body of water is at once a contrived mechanism, with which we attempt to forestall judgment (à la Badiou?) and a hallucinatory exercise into the deconstruction of society, whereby we will succumb to ‘either plastic or dead’.

Nonetheless, a true reading of Fitch is not possible linearly. These poems are not catalogues that mimic Rimbaud’s (much-debated) order; the 42 inversions are purposely jumbled and the titles altered, for example, ‘Marine’ is transposed as ‘Maroon’. These poems filter and slip on Google Translate, as Fitch acknowledges at the back of the book, and what comes across is a sense of echo through which Rimbaud glitters, as Fitch’s ‘i’ simultaneously becomes an entity intrinsically distinct.

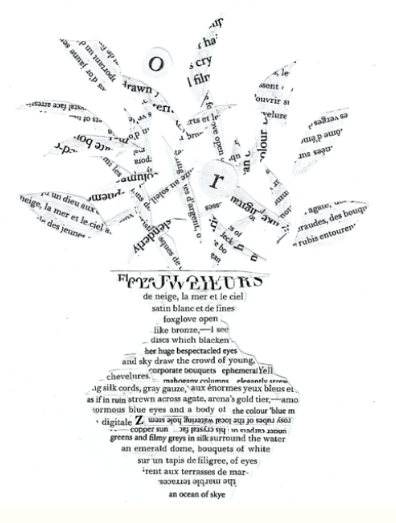

Consider Fitch’s ‘Flooze FLOWURS’:

While this is not the poem Fitch used as his redaction of Rimbaud’s ‘Fleurs’, it is an excellent illustration of his process and use of purple prose; extravagant, ornate and flowery to the point, breaking the flow of the text and drawing excessive attention to itself. In this concrete poem we are privy to the fullness of Fitch’s ‘ephemeralYell’, complete with collage, bilingual interruptions ‘de neige, la mer et le ciel [of snow, sea & sky]’ and excessive use of colour to capture the surreality of Ashbery’s revisions.

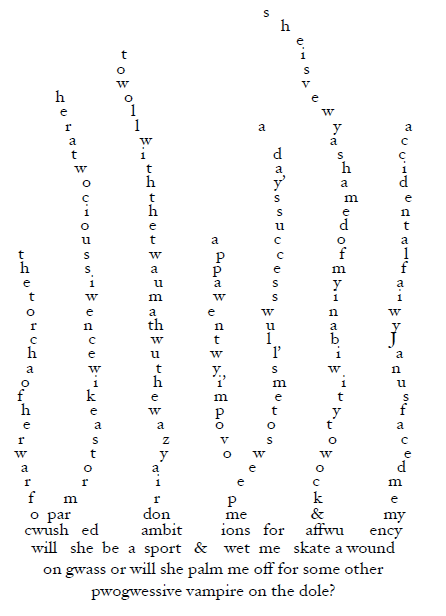

As a collection, we find poems that cross boarders, twist down the page and reflect their title, for example, ‘On Gwass’, which takes the shape of thin, singular bristles of grass trailing down the page towards the glade:

Through this imagery, we can see that each poem figures as a part of something bigger, Rimbaud’s language oversaturated with visual and textual mirage, to the purpose of unearthing a land Down Under that is exploratory in tone and ‘i i in metaphysical travels’. In ‘DEVO LUTIONS’, perhaps my favourite poem of the collection, we are again swept ‘up in the polar rubble’ of Fitch’s inversion and weighed against it. A play on the flow of homophones in ‘Devotions’, society is the subject of the gaze, and the silhouetted form of previous poems uneasily warps and spirals towards us. Unceasing double acts of inscription offer up two re-presentations of ‘DEVO LUTIONS’, as the title breaks the page and insists on being considered in isolation: Devo, and Lution. As we delve deeper into Devo we are positioned to see how society has become trapped in a cyclic religion of ‘of self-worship’, one almost entirely in the virtual as ‘i timely i meme i end’ and perhaps, as the acronym DEVO suggests, devastating ends, ‘air at i price i’s violent’. However, the ‘i i i i i i’ continues to move in centripetal motion and suggests we are not entirely lost, as we traverse the page and coalesce with ‘cc’ to merge into the spoonerism, ‘I see’:

This doubleness emphasises the disharmony and fragmentation of societal existence across all time periods, whether it divides into French bourgeoisie, or the present. Fitch continually observes postmodernity and frames The Bloomin’ Notions of Other & Beau as an inscription onto the societal body of the present and past, one we have the power to change, reliant on the possibility of revo-‘lution’. In the end, ‘DEVO LUTIONS’ is more than an act of resonance, it is consistent throughout the entire collection, positioning the reader to see their own ‘incomplete c c c c c c c c c c’ and transcend the limitations of a modern ‘daze of body and soul’, self declared as Genius, or is it ‘GEN Y’?

In the end, distinct from other reviews, I chose not to refer to Ashbery’s translations; my singular purpose was to consider how the ‘I’ Rimbaud left us with in ‘I is an other’, had and has the power to illuminate a self-sufficient poetry, a system of signs that is and was without reference beyond the original spore. In The Bloomin’ Notions of Other & Beau, Fitch does just this. Undeniably distinct and uncannily familiar, the fragments imposed onto Rimbaud’s original construction speak for themselves; they do not rely on the precursor text. It’s conceivable that Fitch could have invented a similar sequence without Rimbaud’s influence, but the conversation he carries out with Ashbery’s translation makes it a far more powerful work than if Fitch had attempted to write it alone (‘c Ashbery’).

In Edwards’ and Fitch’s collections, one can observe a similar and continued dialogue of intent that is determined to dive into the language of the past and ascend with an idiolect wholly its own. Their originality, keen ability to listen to language and play with meaning is a true marvel, but it’s their translations/transformations that challenge and defy expectation, as compounded in the third stanza of Fitch’s final poem, ‘GEN Y’:

a sinkhole / promises resounded

& the earthworms began to travel w/ tradition again / asking

do u remember yr body or bodies