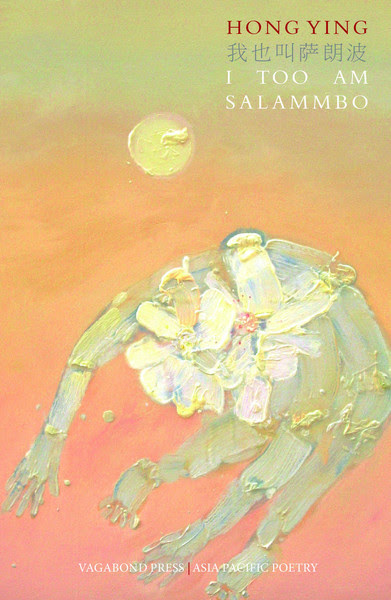

I Too Am Salammbo

by Hong Ying

Translated by Mabel Lee

Vagabond Press, 2015 Hong Ying’s I Too Am Salammbo is a selection of poems from 1990-2012, based on a Chinese selection published in 2014. Though almost all the poems contain conceptual, or imagistic, interest (bar some of the ‘city’ poems: ‘Berlin’, ‘London’, etc.), the formal repetition gets a bit wearing. The collection’s translator, Mabel Lee, uses spacing as caesurae to evoke the possibility of Chinese characters for phrases like ‘moss attracts moss’ (‘Ascending the Mountain’) and ‘painting otters’ (‘Otters’). These are just one kind of moment that happens: many of the poems are far from being as sweetly picturesque, pointing instead to family and sexual trouble, and sometimes both together:

Our lungs

Always wrap around men’s lies and sex organs

Turning I

Confront Mother

And Mother walks away all alone

Before death we sisters will open our beautiful mouths

To spit out one man after another (‘Dreaming of Beijing’)

The use of spacing is effective in aiding line readability. While sometimes it provides merely a slowing down of the line, at others, where the shift in sense between the two phrases is more disjunctive, the effect is one of montage, referring to text, feeling, memory, metaphor:

People walking on ancient land my home village

Other side of the ferry crossing

Stone houses

Furtive lust more than thirty years

Endless eulogies

To one name and torment

Summers of freedom

Illusions of the present

Writing about the black shadows of your wounds

Including the gold tiger in your arms then saying

Winter has ended (‘Writing’)

The concise poem ‘Destruction’ creates its own casket with spacing that might allow exit or entry:

By storing a woman’s childhood

In a jade casket her old age begins

When she dies there is heavy rain

And a swarm of bees circles over our heads

Lee’s critical introduction surmises biographical scenes behind Hong Ying’s poems, particularly in relation to family and men; I think I would have preferred to know less of Hong Ying’s life, or to read about it after reading the poems. In rereading, however, their very strangeness opens up to meanings beyond the personal.

The second and third poems of the book’s first section (the first facing pair), ‘Dusk’ and ‘Fortune Teller’s Dance’ move deftly from a seemingly hopeless immersion in death to a paradoxical, universal vision of new life:

By recalling Father’s death

There is also my death

The blue turns into a chill wind I use a sleeve

To shield my face

Death

Falls into the folds of my clothes

As you said By recalling Mother’s death

There is also your death (‘Dusk’)

Tiny feet pink flowers are in bloom

Buddha laughs

And hell is three feet deeper

To take in more people

Going up the stairs

You tiptoe breathing like a fish

Tiny lips spitting out a fresh world (‘Fortune Teller’s

Dance’)

As we know from the introduction, Hong Ying lived on the Yangtze River as a child; images of fish and river recur in the poems. These can be affirming, as in the quote above, or contemptuous, as in the following, which shows greater identification with the cat than the fish:

I sent the cat to find you

But there was no news all summer

The cat had its four paws etched with your name

The cat said no no

Her eyes brimming with tears

It was also a summer

When I wrote the cat’s words in a book

Who wins who loses? Like a stinking fish

A cruel white colonizes the eyes of the crowd

I lost because I had buried myself under the tree

(‘The Black and the White of Eyes’)

There is a strong relation to the nonhuman animal in these poems: ‘Copying a weasel I stand in the rain knocking doors’ (‘Night in a Small Town’); ‘Gulls in flocks nestle in the hull/Panting as they bend over me’ (‘In Pursuit’). The most powerful for me, recalling Ned Kelly at fifteen (‘every one looks on me/ like at black snake’ from the ‘Babington Letter’) is ‘Among New People’, a worldly allegory:

A black snake and I are eyeing one another

When assailed by a burst of wind and dust

I am borne into the air for half a kilometre

The black snake is dead

I dig a hole in the backyard and bury the snakeskin

Familiar breathing glides over my navel

I’ve buried half of myself

Hong Ying’s distinct relationality extends to objects, such as the dish of ‘Early Morning’, and the photos of the ‘you’ that the narrator eats in ‘The Story of You and Me’; and also to trees:

The tree outside is buffeted by the wind

Without any movement

Duplicated

What kind of tree is it?

What kind of wind is it?

The person speaking is dressed in mourning.

(‘The Elm is Already in Flower’)

This kind of worldliness – or even immanence – is not unusual in Anglophone poetry, but Hong Ying has her own particularity. Her world is not always relationally harmonious either: ‘A pigeon charges at the car window/Angrily protesting/And shouting into his ear’ (‘House with a Dome Roof’); ‘The ant in the grass laughs icily … That wretched ant/Is twitching nonstop’ (‘Dice’). How humorous this is supposed to be I’m not sure; nor of the following:

It’s a girl sitting on a chair watching

Moths five of them

Are flying outside the window

I’m a woman and I have a big mirror

(‘Trap of Mirrors’)

While many of Hong Ying’s titles are perfunctory, consisting of one word, others show us something extra of her (perhaps supported by Lee’s) imaginative and conceptual sensibility: ‘Several Hundred Miles of Emotion’, ‘Swallow-Style Exercise on a Mat’ and ‘The Day Madrid Turned into a Water City’. Yet despite Hong Ying’s distinction we can also read her work in relation to a number of Australian poets. ‘The Elm is Already in Flower’ may recall the deceptive simplicity of Ania Walwicz. But there are stronger similarities to the poetry of Hong Ying’s local contemporaries, Claire Gaskin and Emma Lew.

‘Destruction’, above, is not unlike the poetry of Gaskin, which exploits the surreal effects of juxtaposition as well as the affectiveness of condensation. Gaskin relies more on the long line than Hong Ying, yet we can read both the latter’s long and broken lines as having a resemblance to Gaskin’s cadenced summaries: the title ‘Love Walked Out the Door into the Rain’; the phrase, ‘The bird’s tears try to move an immovable person’ (‘Books and Bird’); and, from ‘Fish Teaching Fish To Sing’, ‘You flee/ You are a fish/ With a broken spine’.

Some interesting poems (from 1992-1995) towards the end of the book deploy their titles and lines in an allegorical-seeming fashion that is reminiscent of Lew. These lines: ‘Blowing perfect smoke rings the white clothes he wears/Make his face look like a piece of anaemic rock’, from ‘Final Episode’ perhaps, but there are even stronger contenders. ‘Toy’ begins:

It’s a meeting you’ll use two plates and two cups

A bottle of potent liquor also there’ll be a deep pit

Fall in and you’ll make bubbles

The mordancy and the slight, prosy stretching of the line correspond. The poem continues:

Figurative images are handier than bundles of light

For carving the width of a house’s shadow

Such lines give the impression of being taken from a great hoard of versatile twigs, or strips, of language: a greater language that is not limited to English, and is perhaps beyond alphabetical and oral/script distinctions. They seem to me worldly, mobile lines, the effect of hundreds of years of reading in translation. There are no gendered references in the first two stanzas of ‘Toy’ (or the fifth and final), but in the third and fourth the figure of a woman appears:

A woman you all know at the conclusion is sitting alone

Suddenly she requests a new topic

It’s as if all the time she’d been hungry for terror

[…]

If this woman could fly away

She wouldn’t think that blossoming flowers could explode

There is enough semantic evidence to suggest that the poem is about a woman wanting to escape from a situation, yet given the context of Hong Ying’s oeuvre it could further be read as describing the pressure any being might be under, or as an allegory for pressure generally. The poem ends: ‘a burst of wild footsteps/ Arrives just at the right time’. The final poem of the section ‘Crows and History’ again has a folk feel. There are no explicit references to crows in the poem – nor to history – it rather tells of an ‘ear injured in a fall’, an ‘ear sprouting green hairs in the sunlight’. In an original extension of surrealism, it is as if the ear itself is having a nightmare: ‘tunes buried in flesh and bones rise in profusion … Only an obese ear is left shouting’. This is not quite the end of the book – there is one line and one section to go – but as a parodic image of global translation turned obscenely (therapeutically?) on itself, I wish it was.

*Michael Farrell has published several books, most recently open sesame (Giramondo) and the e-chapbook enjambment sisters present (Black Rider). Originally from Bombala, NSW, he lives in Melbourne.

**From Cordite poetry Review at http://www.cordite.org.au