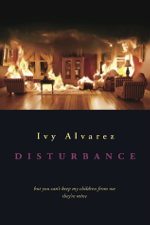

Disturbance

by Ivy Alvarez

Seren Books, 2013

re-membering

by Janet Galbraith

Walleah Press, 2013

How do we truly belong here on this continent, come to terms with our collective and personal history and build a genuine home for the future? And what of the ongoing legacy of violence on an intimate scale, by men against their partners and children – how can this be challenged and interrupted, changed into mutual trust? These are crucial questions; complicated and painful, yet unavoidable. Two new books recognise this and respond with what, to me, are poetry’s great strengths: the generation of an empathic interpersonal encounter, and that aching paradoxical space of both knowledge and productive ignorance.

Disturbance is Ivy Alvarez’s second collection of poetry. Its dedication to Dorothy Porter, Ai and Gwen Harwood is not at all surprising given that, Alvarez’s poems are comparably unflinching, unsettling and precise, exposing the horrors of family violence with an artistry that is always in the service of its compassion. Furthering the link with Porter’s work, it is also a verse novel, but a relatively unconventional one. Rather than following a linear progression, Disturbance throws us immediately into atrocity and its aftermath – the murder of a mother and a son by the father, who takes his own life, leaving a daughter alive. Each poem that follows is a fragment, retrospective and prospective, accumulating a picture of what we want to know but feel disturbed to approach – how did this happen?

When I began reading it, I assumed that the story at the heart of the book was fictional, a composite of many cases synthesised from research. Subsequently, I began to wonder how ‘real’ the poems were; in a way, attempting to measure the gap between poem and reality, I was reaching for the real, yearning for it. But Alvarez notes that Disturbance is ‘an imaginative retelling of and a response to actual events’. Like an exhibition of documentary photography, it presents framed yet incomplete impressions from particular perspectives, which confront us with the existence of the real while acknowledging the gap between an account and its source.

The book is both kaleidoscopic and choral. We are presented with the thoughts and memories of the mother, Jane; the police officers, in their enculturated impotence; the journalists, with their condensations and abstraction; and the son and daughter, with their confusion, bravery and cornered-ness. While the poet’s own aesthetic temperament gives them a certain consistency, each of these character voices is distinct and convincing. The grammar, vocabulary, emotional tone, punctuation and lineation, are all finely attuned to reflect their individual posture and energy. Yet the music of the poems is subtle and unobtrusive; Alvarez doesn’t want anything to overshadow what is being exposed and examined. Sentences are generally complete and naturalistic, a fusion of the mundane and the metaphoric, of the composed and the chaotic, which is quietly chilling:

My dinner rests warm in my belly.

I’ve just come in for my shift.

Familiar smell of old coffee,

stale sweat accumulates,

hovers near the ceiling.

…

‘What is the nature

of your emergency?’

Weariness

wears my voice.

But then she speaks.

I type quickly. I press buttons.

‘What is your address?’

The pads of my fingers prickle,

become slick. Keys slip beneath my skin. (‘Operator’)

Appropriately, there are also occasions where the language itself breaks down or fragments. Here, the poetry draws on an almost risky knowingness and wit, but it never loses its focus and visceral impact, as in ‘The Detective Inspector II’, which begins ‘ – eyes make/in/cre/mental/adjustments/in the dark’. Or, in ‘Hannah’s Statement’, where the breath catches and is held in white space:

once after my brother ran

he placed my hand on his heart

Alvarez’s language is most chaotic and unmoored when we hear from Tony, the father, whose ‘own hands must do something’. His confusion and possessiveness seem fuelled by a profound detachment – of his self from his body and from others. If there is any summary of his motivation to be found, Alvarez provides it negatively, as Tony states: ‘there is no explanation for me’; ‘Real things seem untouchable to me’; ‘I pass for someone ordinary/someone who looks like me’ (‘Tony’). Near the end of the book, we spend quite some time in his mind, which is populated by familiar and archetypal metaphors of ‘red’, ‘hunting’ and ‘dark’, yet also with surreal and unexpected images, such as ‘dust that skims/across your eyeballs’, ‘the subdermal itch’, ‘rank/bin juice’, and an account of the aerodynamics of golf balls. These bring us closer to a kind of visceral intimacy, rather than understanding.

The one poem which I am still ambivalent about is ‘See Jane Run’. Here, the central murderous event of the book is depicted through the truncated sentences and simple language of the iconic children’s characters, Dick and Jane. While only two-thirds of a page and in short paragraphs, this prose-poem seems to be Alvarez’s way of conveying, through parody, the unconveyable horror. It’s an undeniably affecting poem, but one that I am not drawn to read again.

By contrast, ‘Disturbance’ compellingly revolves around a black hole at its core – the mundanity of evil and the seeming inevitability of violence. And the short poem that opens the book, ‘Inquest’ signals silence as a response to inexplicability:

Members of the family wept

as the coroner read out

her pleas for help.

Nothing softened as they cried.

The wood in the room stayed hard

and square.

The windows clear.

The stenographer impassive.

The spider under the bench

intent on its fly.

I say ‘seeming inevitability’, because while there is an echo of a kind of ‘natural’ hunter and prey in the poem’s chilling conclusion, and while the wood stays ‘hard/and square’, the reader is constantly drawn into a state of empathy and resistance. These events, condensed into black text with such articulate and meticulous white space around them, are given to us in all their horror as artefacts, made things, which can conceivably be unmade. It is Alvarez’s great talent to frustrate us, to refuse to provide easy explanations. The only possible response is outside the book.

This ambivalent and productive attitude towards resolution is also one of the key strengths of Janet Galbraith’s first collection of poetry, re-membering, another striking book from Walleah Press. The hyphen is crucial, and not only in the title – these poems are about connection, integration, drawing things together through acts of language. They are poems of process, where the reader observes (and participates in) movements towards healing, both familial and political, but always personal.

In this way, re-membering often reminds me of elements of Adrienne Rich’s poetry, where the public political world is always erupting into the quotidian, revealing the interpenetration of these spheres.

Galbraith is a tireless advocate for the rights and wellbeing of asylum seekers, including the Writing Through Fences project, so it is no surprise to see political concerns throughout this book, and an awareness of how language can make, unmake and remake. The poems touch on family violence, mental illness, hospitalisation, inherited trauma, belonging to land and country, as well as asylum seeker policies. But they are infused with a thoughtfulness and empathy, rather than didacticism.

The language here is reflective and poised, yet with an irresistible sense of immediacy and intimacy. Galbraith writes from places deep inside the body, places of hurt and desire. There is much at stake. But it is in a kind of post-confessional mode; she is not determined to reveal everything, but is forging a workable path forwards, recalibrating inheritance. The poems are generous and explicit, while always maintaining a productive gap between what the poet knows and what the reader might infer:

It is not that I forgive

your needy presence

the tortures

you placed upon my body

fed into my soul.

You who could have been

as the yellow box tree

outside my window

nourished by the decomposing debris

of what has been. (‘Something Other’)

The addressee of this poem is never named, which makes reading the poem feel painfully intimate, almost voyeuristic, while paradoxically also giving it a sense of mobility that allows the reader to enter into it entirely – Galbraith’s ‘you’ is also my ‘you’. This is true of the collection overall, but occasionally we come upon poems which are very particular, such as ‘A shared knowing’ and ‘Listen to the children’, which quote from the poet’s mother and sister. Here, the vernacular is immediately familiar and moving (‘Mum can you do something nice for yourself today?’ and ‘I am lookin afta Janet’). The quotes are repeated, almost to the point of deconstruction, which amplifies the impact of what is left unsaid.

Galbraith’s meditations on personal history are interwoven with images of the non-human world, so that each speaks to the other, revealing connections and separations. In ‘The Pond’, the poet stands ‘in mud up to [her] thighs’, finds an old nail and feels ‘the pulse of stories’. The mud and the nail are actual and physical, while also pointing outwards to emotional and political realities. In her evocation of the human within nature, Galbraith at times edges towards romanticism, but her matter-of-fact delivery, which is also arrestingly clear and musical, ensures that the reader is placed within an encounter with the real. Birds appear often, never quite motif or symbol, but invariably in their actual presence. They offer not a way to escape from the world but a way of being able to live here:

And the magpies, the song and quarrelling of the magpies,

gurgling their song deep in their throat til it comes out open

and melodious. The day is here they call, the day is here. They

aren’t calling to me. I see the world go on without me …

… like that poppy popping

up in the weedy lawn – bright red, suddenly there. Not

blooming for me, but I noticed,

regarded its life, regarded its song. (‘A love poem’)

Galbraith does not hesitate to use words like love and soul, as well as shit and cunt. In a sense, re-membering is an anti-poetic collection, and all the more poetic for it. Its primary focus is life rather than language; therefore, while its attention to language is profound, the poems are always viscerally felt. The poems often operate in the mode of mantra or prayer, journal entry or mini-essay. The poem ‘My body’ consists mostly of the refrain ‘my body my solace/my body my memory/my body’, a repetition that demands sensitivity and a slowing down on the part of the reader. It is a powerful poem of resonance and sound, resting uncomfortably on the page.

While there is overall a focus on the bodily and personal resonance of words, re-membering also includes some poems that show an alertness to the physicality of the page. ‘Disappearing Darling’ begins indented, then jolts to the left margin and the right, to drift slowly down and left – river-like, precipitous and sensual as the body it conjures. ‘Kookaburra’ throws the syllables of the bird in an arc across the page. ‘My friend’ is less surprising in its shape, with its curve echoing the pregnancy it describes, but effective and affecting nonetheless.

The very satisfying modesty and minimalism of these poems is only occasionally undercut by the inclusion of footnotes, which at times imply an overly enthusiastic determination to ensure the reader understands Galbraith’s intention; but this is a minor qualm, more of design than substance. re-membering is a book of poetry that understands ‘that to bring back the dead/is a slow and gentle thing’ (‘that one’). The dead, both departed people and unspoken experience, are brought into the light of language. This is poetry not as therapy but as an essential part of re-knitting the fabric of life. This re-knitting is by necessity incomplete and paradoxical, and (as with Alvarez’s writing) the reader is implicated and involved while the potential response is outside the book, in silence. Perhaps this poetics can best be summed up by quoting the final section of Galbraith’s poem, ‘Mother Love’, where parentheses allow the reader to experience both speech and silence: these ‘borrowed words/that soothe the fear/of speaking//what must (not) be said.’

*Andy Jackson’s collection, Among the Regulars (papertiger media, 2010) was shortlisted for the Kenneth Slessor Prize. His poems have appeared in Heat, Going Down Swinging, Island, The Age and Mascara. In 2011, he was an Asialink resident at Chennai, India, where he began a series of poems exploring the medical tourism industry. He blogs at http://amongtheregulars.wordpress.com

**Taken from Cordire Poetry Review at http://cordite.org.au/reviews/jackson-alvarez-galbraith/2/