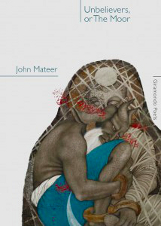

Unbelievers, or ‘The Moor’

by John Mateer

Giramondo, 2013

Emptiness: Asian Poems 1998-2012

by John Mateer

Fremantle Press, 2014

In his two most recent books, the prolific John Mateer presents work developed over the long haul. His concluding essay in Unbelievers is a reflection on the seven years of writing behind that body of work, and Emptiness emphasises in its subtitle the 14-year scope of that collection. Despite the years of writing they represent, both collections bear a freshness of focus, expressed through Mateer’s formulation: ‘the irony of Elsewhere’.

As the the books’ titles suggest, an idea of ‘the East’ is central to Mateer’s project – one concerned with invisible histories, cultural translations, meetings and exiles. Barry Hill’s endorsement of Emptiness lauds Mateer as, ‘the best guide I know to the poetics of travelling in what we call Asia.’ While Hill rightly directs our attention to the invented nature of the zone known as ‘the East’, I’m inclined to suggest that rather than a guide, Mateer’s work represents a poetry of unsettlement, where constructs of both ‘East’ and ‘West’ become equally disorientated. Calling into question the historical contingencies of territory, Mateer’s poetics are alive with the contradictions and contested histories embodied by particular places. More than guiding, therefore, the poetic gestures are archaeological; disturbing and unsettling the surface meaning of ‘Elsewhere’.

One of the main features of Mateer’s poetics of unsettlement is a conceit I will describe as ‘decomposition’. Appearing in various guises across both books, decomposition represents an ephemeral, ironised state in which the significance of an historical or formal construct is revealed at its moment of disappearance or decay. Unbelievers foregrounds this process in the book’s third poem, ‘The Books’:

Not all books were thrown on the bonfires.

Some, as Ibn Zunbul recounts, were stored in abandoned mosques.

Our Traveller, hearing of this, was led to a mosque,

And through the keyhole saw nothing,

But heard – not wind – the rustle of worms.

Maybe, he thought, all books are the Uncreated?

The poem’s emphasis rests not upon destruction as such, but rather the temporal process by which things eventually become undone. When things decompose they become something else, but what they become often tells us much about what they were. This process of metamorphic change can illuminate the elemental parts of the whole. In chemistry, ‘decomposition’ is a term that generally appears with an object, denoting an analysis of the constituent components of a substance (for example, bacteria decomposes milk into its solid and liquid elements). I borrow this particular meaning of the term to suggest that Mateer uses poetic language to ‘decompose’ history’s manifestations – the nations, states, empires and languages that result from the conflation of space with ideology. The narrative of conventional history transforms into a narrative that reveals gaps and contradictions. In Unbelievers afterword, Mateer comments that:

You could say I am interested in lost histories. I wouldn’t really see it like that … I wouldn’t think so much in terms of lost histories, rather in terms of histories that appear and disappear, and histories that are influential even if invisible.

Drawing a swift analogy between history and language, and echoing the writings of Daniel Heller-Roazen, Mateer continues that as with history, it is never entirely clear where one language begins and another ends. Similarly – and intrinsically to Mateer’s work – poetics mirrors this horizon of appearance and disappearance:

We have the material – the form – of how we think words should be composed to be a poem, and those words themselves, whether naturalised loan- or foreign-words, all that elusive material. And besides, both might come to us twinned in the media of sound or writing, with their own heritages and constraints of performance.

Decomposition acquires layered meanings then, relating to a notion of historical analysis, but also alluding to the poet’s approach to formal composition. The poems in Unbelievers and Emptiness develop a compact between the two, where the functions ‘analysis’ and ‘composition’ propose analysis as decomposition. The figural manifestations of rotting and wearing away are reinforced by the use of decomposition as poetic method, which positions the material poem at its own reflexive point of decay.

The actual term ‘decompose’ appears in the seventh poem of the ‘Monsanto’ series of Unbelievers:

Roof, lime-lichened tiles and rotten beams, caving-in,

then the walls, maybe, though they decompose like music

The series comprises of twenty-one short, untitled poems enigmatically related to the contemporary terrain of the Portuguese village of Monsanto. Superficially an account of a location seen through a traveller’s lens, on another level the poems are highly attuned to the temporal dimensions of place. At times the speaker recalls an abstract journalist, a poetic foreign correspondent reporting ‘at the scene’. On one hand there is an imperative to mimic conventional journalism to tell a story as it is happening. Bold opening lines such as, ‘You are still dreaming’, approximate journalism’s perpetual present through the continuous tense. On the other hand, time fills numerous dimensions – it has depth and solidity, it inhabits the landscape. The speaker of the Monsanto poems reports a split, spatialised time:

Two bell-towers,

both ‘clocked’.

Between each

pealing of their hour

a few minutes’

discrepancy that

you allow to be

infinite, or

Monsanto

As with the line, ‘decompose like music’, the pause between the two bells expresses decay through sonic metaphor. The poetic utterance is characteristically Mateer: matter-of-fact, while at the same time firmly abstract in fixating on this moment between meaning and un-meaning. The poem produces an imaginative interval that spans the ideal and the actual (the infinite/Monsanto). Placed at the edge of temporality, the speaker initiates a decomposition of Monsanto’s history. In the interval between the two bell-towers, the speaker reports at the scene of history’s unmaking. But what is the scene at Monsanto? What has happened?

Unbelievers collects its poems following a geospatial logic, with headings named after historically-loaded locations such as Al-Andalus and Meydan, as well as generic non-places such as ‘the mall’ and ‘the bridge’. Like many of the locations that organise Unbelievers, Monsanto represents a contact zone. The Portuguese village was recaptured from the Moors by the troops of King Afonso Henriques in the twelfth century. The ‘Monsanto’ series alludes to the symbolism of this act, focusing especially upon the ironic capriciousness of historical determinism:

The mountain as dice-thrower:

One toss: a crown of boulders.

Another: a castle

Who is there to read the dice?

Who to win or lose

The allusion works not only in relation to the broader recapturing of the Iberian Peninsula, but also as a precursor to the West’s conquering of the globe in the centuries to come. The other geographical excursions of Unbelievers similarly consider the boundary implications of conquering and defeated empires. When does a culture really end or disappear? Where do the defeated go? Perhaps the spectral presence of an obsolete ‘enemy’ remains embedded within the present. Mateer’s poetics have this ghosting occur through ritual (‘join in flinging down/ the terracotta pot of Spring flowers/ at the enemy who left centuries ago’), the psychic charge of ruins (‘Gloaming is the room’s/ natural state’), and visceral, atavistic clues (‘Between us she is Latin, a dark metaphor’).

Loose among these ghosts is an enigmatic and elusive conviviality, described in the afterword as the ‘lost ideal of cohabitation between West and East’. These historical sites of conquest and reconquest were also places of exchange and hybridity – the everyday contact of shared lives. The convivial ideal is not relegated to the past but brought into Mateer’s poetic present. Despite the recurring ‘wandering stranger’/‘unbeliever’ figure, which across both collections nods to an expectation of ‘otherness’ in scenarios when west meets east, both collections privilege situations that undo otherness through an emphasis on fleeting convivial moments. Unplanned meetings, shared meals, brief sexual encounters and so on all allude to what the sociologist Les Back, borrowing from Deleuze and Guattari, describes as intermezzo culture. Defined as much through its discontinuity as its ecstasy, the notion of an intermezzo culture gestures at the embodied magic of temporary affiliation. The social terrain of Unbelievers and Emptiness is peopled by expats and exiles that are most often defined by their roles in a transitory globalisation: translators, interpreters, reporters, photographers, scholars and writers. There are also tourists, taxi drivers, sex workers and pimps. These subjects gather in places that temporarily engender intimacy, where individuals may suspend their often historically determined antagonisms to allow an alternate conviviality to prevail.

In Emptiness, the poem ‘In the Pleasure Quarter’ draws the reader into such an intermezzo scene, before a nightclub in Shinjuku:

Being foreign is the democracy that allows the Nigerian,

in all the accoutrements of a gangsta, to address me as brother

and offer a special discount to a nice place where the girls are all foreign.

[…]

We are, perversely, brothers: of the same continent,

slave and master, ear and mouth

[…]

Our common tongue is illusory, necessary, a kind of coin

minted by being stamped on.

The scene impresses that this ‘lost ideal of cohabitation’ is perhaps destined to reappear only in snatches of discontinuous reality. Conviviality, the occasion to address another (an other) as ‘brother’, is brief and contingent instead of lasting. The irony of the conditions that govern global conviviality is not lost on the speaker – the repetition of ‘foreign’ highlights the unexpected ways distance can double back on itself, delivering momentary glimpses of a deferred intimacy. Another intimacy, an illusory and necessary common tongue, is produced as it is destroyed, ‘minted by being stamped upon’. The poetic choice – to show meaning acquired through a repeated act of insignificance (with tones of violence), an act that will eventually wreck or wear away the thing itself – is consistent with Mateer’s unifying trope of decomposition. In ‘The Vase,’ an evocation of the slave’s voice prompts an unmaking of the vase by the master. Like Unbelievers, Emptiness also emphasises the transformative point between appearance and disappearance, making and unmaking. A variation on the term ‘decompose’ appears again in ‘Lily’, which subsequently presents a euphoric claim on utterance: ‘decomposing, formless, a bad character … Her empty room is filled with Voice! ’ Faced with real or figurative extinction, Mateer shows language gaining meaning through its moment of unmeaning. Dwelling in the brevity of such unnamed moments, the speaker reveals a poetic strategy based around a suspicion of unchanging constructs.

A suspicion of conventional meaning lies at the heart of Mateer’s poetry, which manifests in an allusive, fragmentary poetics. But it would be wrong to suggest that the poems in these titles are obscure or distancing, for Mateer’s deployment of decomposition is perhaps most compelling in his use of conversation as poetic strategy:

The Poet

had found himself speaking of the possibilities

he had lost: not knowing a Nguni tongue, being a nobody

even among the ghostly Australians.

‘Times change, hey,’ the Translator said, discoursing

then on his other lives (‘The Translator,’ Unbelievers)

Seeming reproductions of a conversation may lull the reader into a comfortable mode of narrative reception, or pleasurable eavesdropping, but Mateer’s effect goes beyond these states. Drawing focus to their temporary intimacies, their weak knowledges, their sense of language in decay – already in decay from the moment a word is spoken – Mateer’s fixing of conversations to the page asks the reader to consider the improvised nature of meaning. Are the hardened categories of ‘knowledge’ simply the net product of repeated acts of spontaneous meaning-making, the result of having the same conversation over and again? What changes are brought about by a different utterance or conversation?

It is difficult to know what to say about Orientalism here without reducing Mateer to an over-simplified category. The poems show elements of a critique of the Orientalist perspective through an ironised performance of knowledge, unearthing and unsettling the discursive means by which ‘the West’ makes ‘the East’ its other. Perhaps most significantly, Mateer’s geographical zone is temporalised, presenting an East in the flux of a changing present in stark contrast to the ‘unchanging’ stereotype that is usually affixed to ‘the Orient.’ But to say that Mateer solely critiques Orientalism perhaps ignores the scope of his fascination with the totality. The very inescapability of a stereotypical Orient – lurid, unknowable, inexplicable, sexual – continues to seduce even as its political legitimacy disappears. It is this inescapability that frames Unbelievers and Emptiness. Mateer’s recent collections thrive around this ironic position, and the poetry proceeds in nuanced and reflexive modes in response to identity, place and history. Driven by clarity of aesthetic vision and depth of philosophical inquiry, Mateer’s latest poetry self-reflexively decomposes at the site of composition, unearthing the antimonies at the heart of knowledge.

*Lucy Van was a child in Perth in the 80s. She learnt to swim in the Indian Ocean and learnt about poetry and music from the friends she grew up with. She nearly began a job in publishing before deciding to move to Melbourne to write her thesis on post-colonial poetry. She eventually finished her PhD after having a child and getting a job at the University. She co-founded the LiPS poetry group with George Mouratidis and works on Peril Magazine and Mascara Literary Review.

**Taken from Cordite http://www.cordite.org.au